History pushes us around. It bullies. It tells us, again and again, that ‘not everyone’s destiny matters’. But identity is rooted in history, and so history cannot be escaped. Aboriginal Victorians continue to speak back: oral histories, art practices, storytelling, biography and autobiography announce ‘we have survived’.

But to survive means to ‘continue to live or exist, especially in spite of danger or hardship’. It is not enough just to survive: the children’s voices in the Ngaga-dji report tell us that they want more than this. As academic historians, Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal, what can we do to help children thrive?

In this article, inspired by the young voices of the Ngaga-dji Report, we explore two related questions about history and its practice. First, how can we, as historians, help to write and disseminate histories that restore and recognise Indigenous humanity? And second, how can we help Aboriginal people in Victoria to tell their own histories?

Restoring humanity

Aboriginal children in Victoria are still confronted with histories that erase, stereotype and devalue Aboriginal culture and agency. As Murrenda reports:

At school I learnt that people hate blackfullas. I learnt that I should be ashamed of who I was, reject culture, not be like ‘those’ blackfullas. I wrote essays about Captain Cook, a happy white history where my people didn’t exist. The hate was so strong I felt like I was drowning in it … that hate … swam through my mind until I believed it, accepted the stigma and stereotypes the world had told me about my people.

Indigenous historians record the sophistication and complexity of Aboriginal economic, social, political and cultural relations, developed over many tens of thousands of years and since invasion. As historians cease to privilege textual evidence about the past, and to accord more weight to oral, visual, archaeological and cultural sources, they come to know different, richer, histories. Increasingly, knowledge of ‘Aboriginal’ history is also recognised as central to the ‘Australian’ history written by (Indigenous and non-Indigenous) academics. Such accounts of our shared histories are becoming more widely known thanks to their dissemination by writers like Bruce Pascoe. But it is important that such recognition does more than simply add another layer of complexity to Australia’s history: instead, it must transform both that history and our uses of it.

The impact of an unknown Indigenous history is everywhere, in unspoken bias, increased surveillance, narratives of Aboriginal justice, and informs deathly silences that were and are still perceived to be ‘in the best interests of the child’.

The Ngagi-Dji report lifts the veil on Indigenous children’s experiences (their histories) within the justice system. Their voices are central to a narrative that is indeed about them and their lives. It is shocking to consider however, that these Indigenous children are only the lead actors of this report because ironically, they are the most impacted and marginalised by current justice system processes: because they are Aboriginal.

Indeed, too often, the history that children absorb, that buffets the identities of Aboriginal Victorians and burnishes the prejudices of non-Aboriginal people, reduces Aboriginal people to bit players, conforming to tired and misleading tropes, accorded neither human sensibilities nor human emotions.

History-makers must not pretend that the suffering of Aboriginal people and children rests in the past. History, it seems, is repeating itself and to ignore this, is to relegate their experience, and thus the creation of history in the present. It is to place Aboriginal people ‘outside of history’, yet again.

The Ngagi-Dji Report shows us that the damage wreaked by such denigrating stereotypes extends far beyond the schoolroom, shaping how young Aboriginal people see themselves not only in relation to history, but also how the criminal justice system sees them. How can historians respond? Historians are asked to tell the ‘truth’ about our past. But what does this mean? How can history tell the truth and not inflict harm? How can misrepresentations of ‘truth-telling’ be redressed? How can historians, especially historians in universities, champion the humanity, relationality, diversity and nuance of Australian Aboriginal peoples and their histories while remaining ‘truthful’ to the impact of invasion that Aboriginal Australians are still recovering from and experiencing?

Grace Karskens, in her book, The Colony, shows that sources created by settler colonisers can sometimes help. She draws on Watkin Tench’s 1791 account of travelling into the inland country of the Dharug mob, alongside his Eora companions. Tench was surprised to find how well the two groups could communicate and understand each other: reminded that cultural and linguistic diversity need not diminish the importance of shared humanity.

It is clear that the Eora men were also in strange and unfamiliar country, but they nevertheless successfully mediate the meetings with Boorooberongal man Bereewan, and later with Gombeeree, his son Yellomundy (both were renowned karadju or doctors), and his grandson Deeimba. Tench busily noted some similarities and differences: their foods were small animals and wild yams, rather than fish; the men had not lost a front tooth like the Eora. But what struck him most was the fact that these people used different words, yet they ‘understood each other perfectly’. The locals related stories about wars and conflicts over women; the coastal men told them of the wonders of Sydney and Rose Hill, those rich sources of food. That night, the Europeans and the Aborigines slept together round the campfire. The wakeful Tench watched Yellomundy in the firelight, cradling Deeimba in his arms, carefully moving the child before he turned in his sleep.

At a moment of settler recognition, Tench’s observations reveal the diversity, complexity and interrelationships of not only Eora and Dharug societies, but also settler relations as well. His comments on a father’s solicitude towards his child speak to the recognition of a common humanity and sensibility. Aboriginal children – and their non-Aboriginal peers and teachers – need histories that restore richness, sophistication and dignity to Aboriginal families.

It is important for historians to look beneath ‘dangerous’ or ‘difficult’ narratives.

We have not yet done much to help Indigenous young people to navigate their histories. Sometimes, the most obvious stories do not present a balanced history. For example, how can we reframe youth justice narratives beyond violence and incarceration, and beyond a dominant narrative of the settler state seeking justice against Aboriginal perpetrators? Might we shift the questions to: what structures prevent this young person from being supported? Why is this family suffering? What structures harm Indigenous families?

Providing resources

Academic historians must work to locate evidence that presents the history of Aboriginal peoples as just as complicated, contradictory and illuminating as all other histories of humanity. They must also, as the Ngaga-dji Report so devastatingly underlines, find better ways to disseminate that evidence, and to make their interpretations of it accessible to children, community and teachers.

Recurring throughout the Ngaga-dji Report are the voices of Aunties and Uncles who have helped Victorian children and youths to discover, and to own, a history that might nurture their own storytelling. Academic historians must support the repatriation of stories back to Victoria’s Aboriginal families and to Aboriginal communities; they can help to shift the burden of history away from a select few.

By prioritising a diversity of history-telling and narratives that speak of agency, humanity, endurance, diversity and culture, whether Indigenous-led or otherwise, across collections of sources, teaching or writing, university-based historians can help promote the living experience of Aboriginal people beyond the academy. Such endeavours must be generational and move beyond current notions of collaboration. Historians must empower and make room for Indigenous historians, who must be free within and beyond the academy to tell history that is theirs. If we fail to take responsibility for the writing of the past, or to lay foundations for future history-makers to thrive, history will continue to bully us.

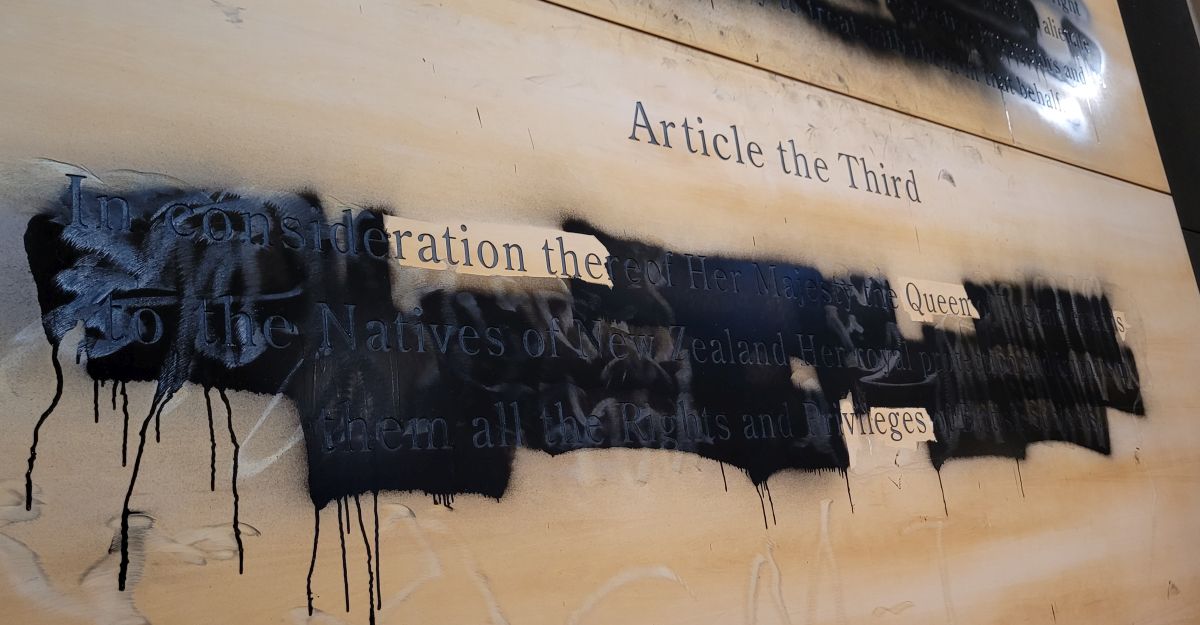

Cover image: Jacob Komesarof, Koorie Youth Council

Read the rest of Reflections on Ngaga-Dji: listening for change, edited by Sophie Rudolph and Claire Loughnan

Read the rest of Reflections on Ngaga-Dji: listening for change, edited by Sophie Rudolph and Claire Loughnan

If you enjoyed this special edition, subscribe and receive a year’s worth of print issues, the online magazine, special editions and discounted entry to our literary competitions